Matthew Romaniello (Odgen, Utah)

"This distemper draws its origins not from Turkey but from America": Russia’s Plague Response, 1771-1772

20.07.2023 16:15 Uhr – 17:45 Uhr

Oberseminar der Professur für Geschichte Russlands und Ostmitteleuropas in der Vormoderne

Die Veranstaltung findet von 16-18 Uhr per Zoom statt:

Meeting beitreten

Meeting-ID: 659 7144 5334

Kenncode: 899101

Abstract

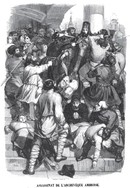

One of the more predictable outcomes of Catherine the Great’s Russo-Turkish War (1768-1774) was the return of the bubonic plague to the Russian Empire. It was the third time it had happened during the eighteenth century, but was by far the most deadly outbreak that century. After the plague reached Moscow, a failed response by local officials to stem the danger led to the infamous plague riot in the late summer, which resulted in the death of Moscow’s archbishop among other city officials.

The European medical community framed the Russian Empire as a laboratory for neo-Hippocratic “cold” diseases, including tuberculosis, scurvy, and catarrhs. The arrival of a “hot” disease such as the plague confounded medical expectations, and delayed an effective response beyond the imposition of a quarantine along the Ottoman border. In fact, physicians working in Russia even argued that the outbreak was not a “true” plague but rather an unknown disease arriving from North America via the ongoing explorations of the North Pacific. Therefore, it was a “cold” disease. When medical authorities finally accepted (after the riot) that it was the plague, local cures, particularly extensive use of juniper berries, was offered as the best therapy for resolving the danger. It would not be until more than a decade after the plague, during the infamous “Russian Catarrh” of 1781-1782, that contagionist ideas began to displace the previously popular neo-Hippocratic arguments, facilitating the state’s adoption of more effective treatments for its disease burden.

By considering the plague of 1771-1772 in light of contemporary medical knowledge, this paper will connect the views of Russia’s climate and its effect on the bodies of imperial subjects to the broader European medical and scientific discussions of the late eighteenth century.